The Catholic Birth of Modern Science

Modern narratives often cast science and religion as opposing forces, locked in an eternal struggle. The Church, we are told, feared the microscope, suppressed free inquiry, and clung to dogma in the face of evidence. This popular myth, however, crumbles under scrutiny. In truth, modern science was born not in spite of the Catholic Church, but because of it.

At the heart of the scientific revolution was a singular conviction: the universe is intelligible, ordered, and governed by discoverable laws. This was not a pagan idea, nor an atheistic one. It was Christian to the core—and Catholic in its intellectual and institutional roots.

![]() Ordered Creation: The Theological Basis for Science

Ordered Creation: The Theological Basis for Science

The ancient world had no unified concept of natural law. Pagan gods were capricious and the cosmos mysterious. Eastern philosophies often viewed the world as an illusion or cyclical in nature, not something to be studied for universal truths. Science requires the belief that the world is not only real but reliably structured, governed by laws that apply everywhere and always.

This revolutionary shift in worldview was birthed in the crucible of Catholic theology. The Church taught that God is not only omnipotent but rational, and that He created the universe through His Logos—the eternal Word, Christ. As the Gospel of John proclaims: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… All things were made through Him” (John 1:1–3). The Greek term Logos implies not only speech but reason, logic, and structure.

Catholic theology insists that creation is good, ordered, and comprehensible. As St. Augustine declared, “The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only one page.” The world, like Scripture, could be read and understood. It had structure and coherence because its Author was rational.

This belief directly inspired generations of Christian scholars to study nature not as a threat to faith, but as a pathway to it. In other words, the foundational ideas that made scientific inquiry possible were theological before they were empirical.

![]() The Church and the Scientific Method

The Church and the Scientific Method

Science is not just data collection. It is a disciplined method of inquiry, involving hypotheses, experimentation, and peer review. And it didn’t arise spontaneously in the Enlightenment. It was systematically developed within the intellectual environment of the Catholic Middle Ages

Roger Bacon (c. 1219–1292), a Franciscan friar, is often called the father of empirical science. He emphasized experimentation and precise observation, building upon Aristotle but refining him through Christian theology. Bacon believed that “truth is the daughter of time” and that God had given humans faculties to explore nature.

Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, introduced what we now call the scientific cycle: forming a hypothesis, testing it through experimentation, and drawing conclusions. He applied this especially in optics and mathematics.

The Church’s university system provided the infrastructure for intellectual inquiry. Unlike ancient academies or Islamic madrassas focused narrowly on jurisprudence, the Catholic universities promoted the trivium and quadrivium—grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy. These formed the foundation for later specializations in chemistry, physics, and biology.

By fostering debate, dialectic reasoning, and logic within a theological framework, the Church created a culture of disciplined curiosity. This was the womb of modern science.

![]() The Galileo Controversy: Caution, Not Conflict

The Galileo Controversy: Caution, Not Conflict

No discussion of the Church and science is complete without addressing the Galileo affair—perhaps the most misrepresented event in the history of science. The standard narrative paints Galileo as a bold scientist silenced by a dogmatic Church. But the reality is far more nuanced.

First, it’s worth noting that the heliocentric model was not a new or forbidden idea. Nicolaus Copernicus, who developed the theory that the Earth orbits the sun, was himself a Catholic cleric. His book De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (1543) was dedicated to Pope Paul III. The Church initially welcomed Copernicanism as a legitimate astronomical model.

So why the controversy with Galileo? The Church’s concerns were not theological opposition to heliocentrism per se, but scientific and pastoral caution. Galileo claimed that heliocentrism was a proven fact, at a time when the available evidence (such as stellar parallax) was insufficient to confirm it. Church officials—many of whom were scientists themselves—asked him to present it as a hypothesis until further evidence emerged.

Complicating matters was the Protestant Reformation, which emphasized a literal reading of Scripture. Catholic theologians were under pressure not to appear lax in scriptural fidelity. Galileo, in defending Copernicus, also ventured into biblical interpretation, which the Church regarded as outside his expertise.

Moreover, Galileo’s relationship with Pope Urban VIII deteriorated after he published his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems in 1632. Though the Pope had initially supported Galileo and even encouraged him to explore Copernican theory, Galileo alienated him by placing the Pope’s arguments into the mouth of a character named Simplicio—Latin for “simpleton.” While Galileo claimed it was coincidental, many saw this as a personal insult. This diplomatic blunder turned support into resistance.

It is also often overlooked that Galileo was not tortured, imprisoned in a dungeon, or excommunicated. He was sentenced to house arrest—a punishment that allowed him to continue writing. His later work Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations was completed during this time.

Contrary to modern assumptions, many secular authorities of the time may have treated Galileo more harshly. In an age when dissent often led to execution or indefinite imprisonment, the Church’s response was relatively restrained.

Cardinal Bellarmine (1615): “If there were a real proof that the Sun is in the center… we should have to proceed with great circumspection in explaining passages of Scripture which appear to teach the contrary.”

Pope John Paul II (1992): “The error of the theologians of the time was to think that our understanding of the physical world’s structure was, in some way, imposed by the literal sense of Sacred Scripture.”

Modern historians such as Dr. Maurice Finocchiaro and Dr. Thomas Mayer increasingly recognize that the Church’s actions were shaped by institutional and political pressures rather than hostility toward scientific discovery. The Galileo affair is better understood not as a war between science and religion, but as a tragic case of poor communication, personal pride, and historical context.

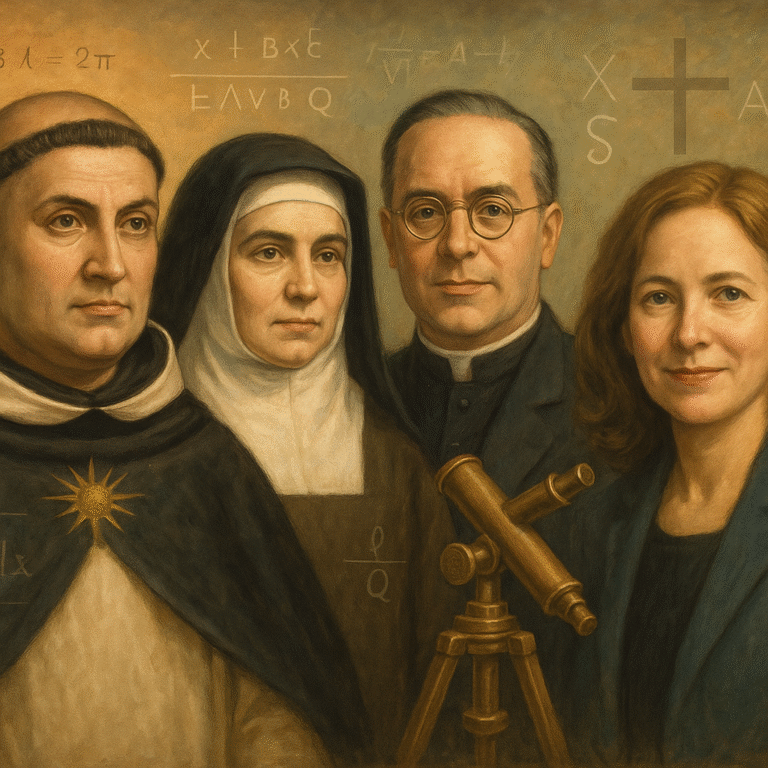

![]() Catholic Scientists Who Shaped the World

Catholic Scientists Who Shaped the World

Far from being marginal contributors, Catholic scientists have been among the most consequential figures in the history of scientific progress—founding fields, transforming disciplines, and making discoveries that reshaped our understanding of the universe.

- Nicolaus Copernicus – Heliocentric model of the universe.

- Gregor Mendel – Father of genetics.

- Fr. Georges Lemaître – Big Bang theory.

- Blaise Pascal – Probability theory, hydraulics, apologetics.

- Louis Pasteur – Germ theory, vaccines, pasteurization.

- Maria Gaetana Agnesi – First female math professor and textbook author.

- Alessandro Volta – Inventor of the electric battery.

- André-Marie Ampère – Electromagnetism (ampere unit).

- Luigi Galvani – Bioelectricity.

- Pierre Duhem – Physicist/historian, demonstrated medieval scientific roots.

- St. Hildegard of Bingen – Botany, cosmology, natural medicine.

- Fr. Athanasius Kircher – Magnetism, geology, linguistics.

- Fr. Angelo Secchi – Stellar classification.

- Fr. Francesco Lana-Terzi – Early vacuum airship and aerodynamics.

- Fr. Marin Mersenne – Acoustics, mathematics.

- Fr. Jean Picard – Geodesy and Earth measurements.

Their contributions testify to a truth too often ignored: the Catholic Church has been not only a patron of science but a participant in its greatest triumphs.

![]() Catholics in Computing and Technology

Catholics in Computing and Technology

While the early history of science is often linked with astronomy, physics, and medicine, the Catholic contribution to modern technology—particularly computing—is no less remarkable. As the digital age dawned, Catholic thinkers, educators, and scientists were not merely passive observers; they actively shaped the technologies that define our world today. Rooted in a tradition that values human dignity, rational inquiry, and service to the common good, Catholic innovators approached technological progress as a tool for both intellectual enrichment and moral uplift. From programming languages and early software education to ethical debates in artificial intelligence and digital evangelization, Catholics have helped humanize technology in profound ways. Whether as pioneers in academic computing or as visionaries using digital tools to proclaim the Gospel, their contributions reflect a continuity with the Church’s enduring role as a guardian and guide of human advancement. The story of computing, like so many chapters of Western innovation, cannot be told without the voice of the Church.

Sister Mary Kenneth Keller – First U.S. woman to earn a PhD in computer science; co-developer of BASIC.

Blessed Carlo Acutis – Used web development to evangelize and document Eucharistic miracles.

Catholic universities and institutions have supported early computing, robotics, and electronics research through academic programs grounded in moral philosophy.

![]() Catholic Contributions to Medicine and Biology

Catholic Contributions to Medicine and Biology

Hospitals were pioneered by religious orders like the Benedictines, Daughters of Charity, and Franciscans. These institutions were not merely places for medical treatment—they were expressions of Catholic charity rooted in the belief that every human being, regardless of status or wealth, possessed inherent dignity as a child of God. Monasteries in the early Middle Ages frequently included hospitia, which offered care for the sick, the poor, and travelers, long before any state-run healthcare existed. The Daughters of Charity, founded by St. Vincent de Paul and St. Louise de Marillac in 17th-century France, revolutionized nursing by emphasizing professional competence alongside spiritual care. This model of holistic healing—body and soul—became the foundation for the hospital system as we know it today, influencing both Europe and the Americas.

Dr. Jérôme Lejeune – Discovered the chromosomal cause of Down syndrome; champion of human dignity in genetics.

Modern Catholic hospitals and institutions continue to promote life-affirming medicine grounded in ethics and reason.

Modern Catholic Scientists

- Dr. Karin Öberg – Harvard astrochemist and convert, studying interstellar molecules.

- Dr. Stacy Trasancos – Chemist and theologian, unifying lab science with Catholic moral theology.

- Fr. Tadeusz Pacholczyk, PhD – Neuroscientist and bioethicist working at the intersection of modern science and Church teaching.

![]() A Cultural Amnesia: The Erasure of Catholic Scientific Legacy

A Cultural Amnesia: The Erasure of Catholic Scientific Legacy

Despite all this, textbooks and popular culture often ignore Catholic contributions. Why? Because acknowledging the Church’s role in science would undermine the myth that religion is irrational.

The truth? Without Catholicism, there would be no scientific revolution as we know it.

![]() Faith at the Root of Knowledge

Faith at the Root of Knowledge

To the skeptical mind, the evidence should be persuasive: wherever you find the serious, sustained pursuit of knowledge in the West—be it in universities, laboratories, hospitals, observatories, or philosophical schools—you will nearly always find the Church not far behind, and often at the very center. The Church did not merely tolerate science; she fostered it, institutionalized it, and gave it philosophical foundations that made systematic inquiry possible. Whether by founding universities, preserving classical knowledge through the monasteries, promoting education among the poor, or encouraging rigorous theological and philosophical debate, the Church consistently acted on the belief that faith and reason are not enemies, but allies in the search for truth. From the earliest cathedral schools that laid the foundation for the university system, to the clergy and religious who became astronomers, physicists, and biologists, the Catholic Church was not a reluctant bystander to the scientific revolution—it was its cradle, its compass, and often its catalyst. The more deeply one studies the roots of Western intellectual life, the more clearly one sees that Catholicism was not an obstacle to enlightenment, but its indispensable soil.

![]() For Further Reading

For Further Reading

- How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas E. Woods, Jr.

- Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths About Science and Religion edited by Ronald L. Numbers

- The Galileo Affair: A Documentary History by Maurice A. Finocchiaro

- The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages by Edward Grant

- Science Was Born of Christianity: The Teaching of Father Stanley L. Jaki by Stacy Trasancos

- The Savior of Science by Stanley L. Jaki

Domus Dei exists to remind the world that the house of God is also a house of wisdom, of science, and of truth. Explore more here!